It’s the day after Lebron James became the all-time scoring leader, and NYU professor David Hollander, author of the new book How Basketball Can Save the World, is telling his class of the same name that he couldn't care less about what LeBron did last night. The topic of today’s lecture is cooperation. It’s the first of 13 principles covered in the book and the class. And while Lebron is known as one of the greatest cooperative minds of his generation, possibly all-time, in his quest to finish the job of all-time scoring leader, the Lakers lost the game. Hollander hammers on this point. For Hollander, there is no basketball without cooperation. Instead Hollander tells the story of hearing a rare radio interview with Bill Russell in the 90s. The host asks Russell how he would stop Shaq, and Russell responds, after 10 long seconds of dead air, that he wouldn’t—his teammates would. This is basketball. This is why Hollander believes basketball has the power to alter the trajectory of humanity towards a more prosperous and equitable future.

How Basketball Can Save The World began as an NYU course in 2020. The first few semesters of its existence were an active experiment to test Hollander’s thesis. It’s part of a larger model that he’s implementing, as assistant dean, into NYU called Real World. The big idea (Real World) is a multidisciplinary approach to education that groups students with A-list executives to solve immediate corporate issues. Within that is the basketball idea which suggests that if the current systems are not working for humanity, perhaps a new world built around the principles of basketball could be one that does. It sounds silly, like the ex-MLB manager turned presidential candidate on the show VEEP who speaks in baseball platitudes to fix America. But break basketball down into 13 principles, which are fully obtainable for the average person, and it starts to feel sensible. Basketball takes cooperation, it requires a balance of force and skill, it balances the individual and the collective, it’s positionless (meaning no specialization like a lineman forbidden from catching a pass), and it’s already a global phenomenon. Go deeper; basketball courts have lower barriers of access on an urban and rural scale. Basketball is gender inclusive. It supersedes language barriers; mime a shooting form or dribble motion in a foreign country and someone will point you toward a basketball court where you’ll further communicate through a shared language of play. Basketball is an antidote to loneliness and isolation. It’s also a place of individual sanctuary. Go even deeper, or rather cosmic, it’s human alchemy and transcendence.

The class is not pure theory. Hollander invites guest speakers who are living proof of his hypothesis. People like documentarian Dan Klores who’s produced numerous basketball documentaries and opened the Earl Monroe New Renaissance Basketball School in the Bronx; a school that teaches young people about the off-court jobs surrounding the game. Hollander’s students interact with Big East commissioners, deputy NBA commissioners, and Nike marketing executives. They discuss how the game alters their interaction in the everyday world with legends like Sue Bird and Walt Frazier, who don’t see a busy sidewalk, but full court press to carve through. And in my experience after auditing three classes, the challenge to prove the theory is not taken lightly. During a discussion with Claude Johnson, executive director and founder of the Black Fives Foundation, he proposed that perhaps “Naismith wasn’t trying to fix a broken world,” as Hollander suggests, but rather, “he was trying to slow the world from breaking.” Chew on that.

The Real World tract emphasizes action. This semester the Basketball class is petitioning the United Nations to approve a World Basketball Day. Each student has to write a letter making their argument for the resolution. (And should you want to get engaged with your own letter, Hollander includes a draft resolution in the book.) The action item is a new edition to the course inspired by a previous experience in which Hollander learned of a small town in Italy that petitioned the Vatican to approve Madonna of the Bridge as the Patron Saint of Basketball. Hollander saw an opportunity to engage his students and through their cooperative international work the town and the class made it happen. In his recognition of the sainthood, Pope Francis said of basketball, “Yours is a sport that lifts you up to the heavens because, as a famous former player once said, it is a sport that looks upwards, towards the basket, and so it is a real challenge for all those who are used to living with their eyes always on the ground.”

Claude Johnson (executive director of the Black Fives Foundation) and professor Hollander in discussion

The book How Basketball Can Save The World is not about how to improve the NBA or fix the amateur dilemma of the NCAA or how to address the problems with AAU. It’s not a manifesto. This is not the new -ism to fear. The book asks why can’t the world be more like basketball? Why should that feeling we get when we play the game be limited to 94 feet? If this feels like a world in which you’d like to live, these 13 principles might just be the blueprint to make it happen.

*****

I spoke with professor Hollander about his book and class, which explores a surprising connection between the times in which we currently live and the Gilded Age of the 1890s. But, we began with the simple idea of self-improvement through basketball, starting small and localized, before getting to the big picture of saving the world.

Was there a person for you who put the idea in your mind of becoming a better person through the game?

Bill Russell and Bill Bradley were articulating things about the way they played basketball and what it taught them in ways that I had felt, intuited, but never gave language to. They were the first people. There are great books. There was John McPhees’ A Sense of Where You Are, which was about Bradley in college. David Halberstam’s The Breaks of the Game was the first time I realized you could talk seriously about this. But I wanted to take it a step further. I’m not interested in the institutional manifestations of basketball: The NBA, The NCAA, The AAU. I’m interested in the game as a social institution, as a way to be a better person.

I extrapolated 13 organizing principles for the 21st century.

What was the seed of the idea that became the book?

The seed of the idea was a course. The genesis of the course was a confluence of me, I believe, doing my job right which is listening to students and locating social currency that allows me to resonate with them on a level that gives them the motivation and means to learn about the things they can apply to make the world a better place and make their lives better. Specifically, I saw the world coming to a broken place. That broken place, I concluded, was the result of millennia of the same kinds of leaders coming up with the same kinds of ideas and fighting about them and landing us in a progressively more broken, more confused, more conflicted place.

I thought what if I somehow took what I feel when I play basketball, which is balance, peace, self-integration, right relations with others, and I know other people feel the same way, and what if I could somehow translate that into a set of values that could guide us to fix acutely 21st century problems? So again, I did my job. Developed a thesis, did the research, and the 13 principles in this book are the result of that work. All the discussions, the guests, and the assignments that me and my students have entered into together.

The decision of 13 principles, can you walk me through that.

I had no number in mind. I’ve called it an homage to the numeric 13 original rules [of basketball written by James A. Naismith]. It is not a direct extension, correlation or anything like that. I just sat down and tried to really think about what does this game stand for? The way it’s played and the impact it’s had on the world and what the world has told us it means to it. I roughed out those principles and then refined them with every conversation and every dig into literature and reading and experience that I could.

Because it does coincide with Naismith’s original numeric rule count, it further speaks to some of the almost mystical overlaps that you continued to discover in your research of Naismith, the man, and the game he invented.

I had no idea how much foresight, how unusual James Naismith was. I do not claim he was a morally perfect person. I don’t know. I do know that his game on a micro level was a response to a very practical problem: find an indoor game. But I believe really his game was a pouring out of his particular lived experience and the social conditions of the time. What his response was was a game that was easy to access, a game that made people think about each other and share, and minimize force and balance it with skill. It was a response to the Gilded Age.

When did this correlation of the Gilded Age to Now begin to take shape for you?

You get lucky. The more I developed the thesis of the 13 principles, I started reading all kinds of people who were trying to solve 21st century problems, people like the economist Dambisa Moyo, who talks about stakeholder capitalism, new kinds of capitalism, ESG capitalism. Different ways of taking our current economic model and making it more invested in communities and each other. She kept referring to the Gilded Age. I said hold on a second. I started to read more about the Gilded Age. I read a great book called The Republic For Which It Stands, which won a history book award. This is like 5,000 pages. Stanford historian Richard White, who basically said the Gilded Age for historians was typically fly over territory. It wasn’t treated as very important. Other big events—World War II, the Revolutionary War, Emancipation Proclamation—which are not unimportant things, but actually the most formative time in this country was the Gilded Age and in that time there was the greatest wealth inequality the nation had ever known. There was the greatest hatred of newcomers and immigrants because there was an unprecedented amount of immigration. There were new technologies which were promised by the new technologists to make everyone’s life better and make it a more democratized time and it was the opposite. It became a hoarding of wealth and power at the top and a resistance to collective labor. Jim Crow laws. Chinese exclusion laws. All this othering. The entire world becoming a tinderbox, heading toward its first all-consuming mechanized, armed conflict, World War I.

Wow. The same language. All the same events. You can take out Carnegie and Rockefeller and put in Bezos and Elon Musk. The parallels are really incredible between then and now. And if you look at the one thing, and I believe we are in a progressively worse version of the Gilded Age, but if you look at the one thing from that time that has actually progressed in ubiquity and influence over the 130 years since it was created, it is basketball. Basketball has gone to more places. Been loved by more people in more countries. It’s had more influence over young people, in fashion and music. It seems to engender a feeling that I talked about in the beginning. I feel really connected to other people when I do this. I feel a sense of sanctuary. Nobody is saying that about monopolistic practices. Nobody is saying that about other things that have shown up again about othering and all kinds of racial, ethnic, and gender hatred.

As a provocation I said, all the other -isms if you mention them, capitalism, socialism, it’s like ‘oh, you’re on that side.’ Ok then, new vocabulary: basketballism. And the 13 principles are the life support system of this Starship Enterprise.

I’m thinking about the shutdown and the response to the shutdown. In a lot of ways the NBA was in the midst of that. In a lot of ways the impact of the social justice movement was elevated from athlete response.

I make it clear when I teach the course and I try to intimate it in the book that this is not about the NBA. One can begin to burden the NBA with the right and wrongs of the game of basketball. The NBA is a business. It’s a hardcore business. It’s an aggressive for-profit concern. As are the other sports leagues. Nothing wrong about it. I’d argue that compared to the other sports leagues, the basketball league has a pretty impressive record in social justice, entrepreneurship and things like that.

The example I like to look to in the shutdown is the incredible refusal of people to stop playing basketball. Publicly to continue playing pick up. Even though it was like social distance or you die. Isolate or you die. We didn’t have a vaccine. We didn’t have any of that. And the one thing people would not stop doing is they would not stop going to public basketball courts. So much so that all over the world, notably the mayor of Chicago and governor of New York, not only did they have to make public statements begging people to not go play basketball, but nobody listened so they took down the rims. That tells you how badly people need to play basketball. And when you need something badly—we’re not talking about an illicit drug, but something good—that means it’s so good, it’s so health giving, it’s so stabilizing of someone’s sanity, it makes them feel connected. It filled the longing that COVID gave us all. I just think it’s one of the unbelievable stories.

When people say “what should we look to after the pandemic?” Nobody talks about that anymore. We seem to be sliding back to a pre-pandemic mindset. I’d really love more study of that need of people to connect—not at the bocce court, not at the chess club—but at the basketball court. What’s that about?

I got back out there when I felt I could. I played with a mask when the rims were restored, until I felt comfortable to play without. I saw someone last week at a run who showed up with a mask on. He’s still here!

Bobbito Garcia was out there [in the pandemic] with no rims, just playing. You know, because it’s the movement. There’s so much that’s happening in that small space with other people that is healthy.

New York City already has so much of the basketball infrastructure in place. I’d call it a great testing ground for the ideas in this book. What’s something this city could apply right now to inch toward a better version of itself?

Make courts accessible. Not just to the elite basketball tournaments. Make courts accessible to as many people as you can as often as you can. I would, as was once before done with Midnight Basketball, I would invest in basketball as a healing, as a social, as a communal tool. In communities where there’s bad relations between law enforcement and the community. Think about how we can use basketball where we want racial ethnic groups from different neighborhoods to get along better. When we want to help newcomers, I mean immigrants, legal or illegal, to find a place to demonstrate their connectedness to others. Think about how we can use basketball. I just think basketball, because it’s a sport so tied to all this other stuff, it’s only seen as an athletic institution and not a social one. I would view it as a social tool.

How can basketball save the world when there are more violent forces like a police state?

What I know is this. Because basketball is a space where people begin to feel a sense of community and empowerment, it’s exactly the kind of space that police states and authoritarian states don’t want people to access. And so, three examples:

One is, and I learned this while researching the book, some of the only people who refused to drink the Kool-Aid in the Jonestown cult were the basketball team that they had formed. Why is that? Well, I believe because basketball opens your eyes to a totally different kind of self. It defies self destruction, it encourages transcendence. I do know that the great story of Lithuanian independence was driven by the basketball team as a symbol of national pride. As a symbol of national pride because the game itself spoke to independence, spoke to freedom of movement.

Thirdly, if you want to look at what has been one space where African Americans, in the United States where race is such a core issue—an unresolved national sin—, basketball has been the space where entrepreneurship, ownership, ownership of self has obtained and become a space of creativity. I see the social impact that the game has had. When you start taking away basketball courts, you start taking away accessible spaces where people can see each other and humanize each other. Humanization is the enemy of authoritarianism.

The sanctuary chapter goes into not just physical, but spiritual, and even surveillance. Can you walk me through the connections that formed as you explored those three ideas of sanctuary?

It seems like everybody you talk to, when you talk about basketball, they say it’s a place I like to go to when I want to escape. A contour of that is the benefits of play in general. Play is a sublime relief from real life. A lot of people say sports is like life. It’s not. The reason we like it is because it’s not like life. Life is sprawling and incomprehensible, impossible to predict. Play is defined in locality and duration. It’s rule based. In life there are no rules. It’s voluntary. [Basketball is] freedom itself. It’s divorced from material gain. Pure play. The pure play of basketball particularly, elevates all those elements because of the small space and you can do it by yourself. There’s an experience that happens in basketball that’s really an elevated sense of that separation from real life.

Why is that a big deal? If we’re constantly in a state of reality, it’s intense. The consequences are dire. Often it means hunger, heartbreak, life and death, illness, shelter. All those basic things. Play is relief from those things. And I said, what else is it relief from? Why do we need relief? Is that so hard to get?

I believe it’s harder and harder to get. In the 21st century I think it is one of the biggest problems we face. There is no space you can go where you can just have your own self to yourself, or have your own experiences that are not surveilled, counted, measured, and fed algorithmically to some force that is harvesting that information to manipulate you. This is not the way a society grows. This is not the way a person finds clarity, peace, and a restorative mental state. I call it fundamental right, it’s also a constitutional right, we have a right to sanctuary. Which means a right to space that no one else gets to enter unless you consent to that. I think that basketball stands for that. I admit it’s an extension of the feeling you get from basketball. Nonetheless, I think consistently people say they get it from basketball and are hungry to have it more. I know why. We’ve gone too far in giving up that privacy and right to protect your own experience in this world.

We create with the hope of a better life, but there’s always a counter force that wants to take your well-meaning thing and use it against you to maintain their power. The example I’ll use is pronouns. Marginalized people were simply trying to create a path towards representation. And that push for progress, a more inclusive America, turns into right wing politicians declaring their pronouns are gun, patriot, and impeach Biden. Basketball seems impervious to the anti-progress machine. What do you think gives basketball the potential to remain that way? How do we prepare for those counter measures?

I don’t mind debate of any kind. I do mind the zero sum game that you’re expressing that if you’re not this then you’re that. I’m hoping that what I’m offering, somewhere in it, I can find something that the person or the force or the organization that says “oh, what you’re doing is X and we stand for Y.” I can say, “but look here’s Y. Right in it. We’re both Ys, man.” This is my attempt if there ever was one to start common ground. I welcome that conversation. I hope in doing so, it exposes those who are not interested in resolution. They are only interested in power, domination, oppression, winning, all these things which really aren’t the destiny of the human condition. They simply aren’t. It’s unsustainable.

Old timers can tell me it’s always been like this and we’ll get out of it. With all due respect to that attitude and perspective, I think there’s going to be significant pain at this epoch if we don’t get it together. I really do. I hope this is just a way to sit at a table.

Can basketball save the Knicks?

[Laughs.] I think the Knicks have vastly improved.

This question is hopefully becoming outmoded.

I think it is becoming outmoded. I’ve seen the Knicks play this year in person. I think they are a talented and competitive NBA franchise. The greatest home court advantage of all time is Madison Square Garden. We’ll see what happens next.

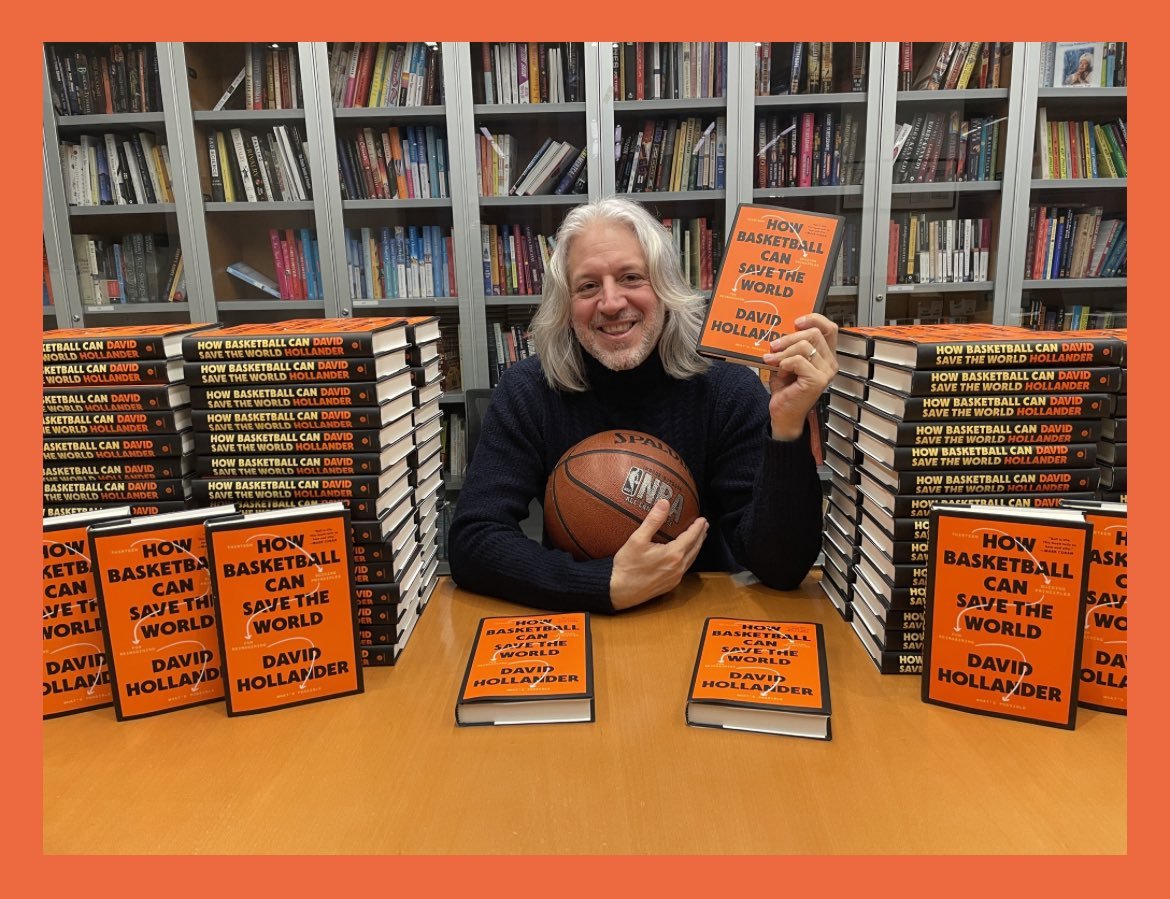

David Hollander’s How Basketball Can Save The World is out now on Harmony Books.

Sacred is an independent basketball space of free-flowing creativity. With limited options to publish these stories professionally, the patronage of readers like yourself offers meaningful support to sustain the work. Donations will go directly toward 35mm film and film processing, investing in future apparel and literary projects, and website service fees.

VENMO: @busy-gillespie

In gratitude,

Blake Gillespie